OVERVIEW (2018)

Early Years

← July 3, 1776

July 4, 1776 (U.S. Declaration of Independence approved) – June 20, 1788

November 11, 1784

James Madison drafts and introduces a “Bill for Granting James Rumsey a Patent for Ship Construction” to the Virginia General Assembly. A similar bill is introduced in Annapolis. Both pass at the urging of General Washington.

Excerpt

“Be it therefore enacted that the said James Rumsey his heirs, Executors and Assigns shall have the sole and exclusive right and Privilege of constructing and navigating Boats upon his model in each & every River, Creek, Bay, Inlet or Harbour within this Commonwealth for and during the said term of ten years, to be computed from the first day of January one thousand seven hundred and eighty five. If any person, other than the said James Rumsey his heirs, Executors or Assigns, shall during the term aforesaid either directly or indirectly, construct navigate, employ or use any Boat or Boats upon the model of that invented by the said James Rumsey or upon the model of any future improvement which the said Rumsey may make thereon, he or they for every Boat so constructed, navigated, employed or used, shall forfeit and pay for every such offence the sum of ⟨five hundred pounds⟩ to be recovered with costs by action of debt, to be founded on this Act, in any Court of Record ⟨one half⟩ to the use of the party who will sue for the same⟨, and the other half to the use of the said James Rumsey⟩.

Provided always that the exclusive right and privilege hereby granted may, at any time during the said term of ten years, be abolished by the Legislature upon paying to the said James Rumsey his heirs, Executors or Assigns the sum of ten thousand Pounds current money in gold or silver ⟨of Virginia⟩.”

Sources

a) “Bill for Granting James Rumsey a Patent for Ship Construction, [11 November] 1784,” Founders Online, National Archives, LINK. [Original source: The Papers of James Madison, vol. 8, 10 March 1784 – 28 March 1786, ed. Robert A. Rutland and William M. E. Rachal. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1973, pp. 131–133.]

b) “From James Madison to Thomas Jefferson, 9 January 1785,” Founders Online, National Archives, LINK. [Original source: The Papers of James Madison, vol. 8, 10 March 1784 – 28 March 1786, ed. Robert A. Rutland and William M. E. Rachal. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1973, pp. 222–234.]

May 28, 1787

Charles Pinckney, delegate from South Carolina to the Constitutional Convention, delivers in the course of discussion: “There is also an authority to the National Legislature, permanently to fix the seat of the general Government, to secure to Authors the exclusive right to their Performances and Discoveries, and to establish a Federal University.”

Sources

a) Farrand’s Records, Vol. 3, page 122; May 28, 1787.

b) United States Constitutional Convention & Farrand, M. (1911) The records of the Federal convention of. New Haven, Yale University Press. [Pdf] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/11005506/.

August 18, 1787

During the Federal Convention James Madison declares “[t]he following additional powers proposed to be vested in the Legislature of the United States that Congress be empowered … to encourage, by proper premiums & Provisions, the advancement of useful knowledge and discoveries.”

Sources

a) Farrand’s Records, Vol. 2, page 322; August 18, 1787.

b) United States Constitutional Convention & Farrand, M. (1911) The records of the Federal convention of. New Haven, Yale University Press. [Pdf] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/11005506/.

January 23, 1788

In Federalist 43, James Madison explains that “[t]he utility of this power will scarcely be questioned. The copyright of authors has been solemnly adjudged, in Great Britain, to be a right of common law. The right to useful inventions seems with equal reason to belong to the inventors. The public good fully coincides in both cases with the claims of individuals. The States cannot separately make effectual provisions for either of the cases…”

Sources

June 21, 1788 (U.S. Constitution effective) – Apr. 9, 1790

June 21, 1788

The Constitution of the United States of America is effective upon New Hampshire’s ratification.

The Constitution of the United States of America establishes the official framework for governing the Nation.

Article II, Section 8, clause 8 of the U.S. Constitution gives power to Congress “To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries” (known as the Intellectual Property Clause).

Sources

The U.S. Constitution is included in the “America’s Founding Documents” collection at the National Archives website. LINK.

Read more about the Clause's origins and early understanding.

Bracha, O. (2008), ‘Commentary on the Intellectual Property Constitutional Clause 1789′, in Primary Sources on Copyright (1450-1900), eds L. Bently & M. Kretschmer, www.copyrighthistory.org (browse by “Commentaries” then by “Legislation” then by “U” and look for “U.S. Constitutional Copyright Clause 1789” and finally the link “1789 * : “The Constitutional Copyright Clause”).

March 4, 1789

The Federal Government of the United States of America begins operation.

Read more about this day

Jim Martin of the Law Library of Congress tells the story of the Continental Congress ajourning sine die on this day, thereby activiting the Compromise of 1790. His post can be found on the blog page of the Law Library. LINK

April 30, 1789

George Washington is inaugurated as the first President of the United States. His administration lasts until March 4, 1797.

Augusst 28, 1789

Thomas Jefferson writes (from Paris) to James Madison suggesting adding a patent term to the Bill of Rights.

Excerpt

Source

September 18, 1789

William Hoy and James Rumsey petition Congress to secure the exclusive right to their inventions.

Excerpt

Journal of the House of Representatives of the United States, 1789-1793

FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 18, 1789

A petition of William Hoy was presented to the House, and read, setting forth that he has discovered an infallible cure for the bite of a mad dog, and praying that an adequate compensation may be made him for his labor and assiduity in the discovery, which, in that case, he will make public.

Also, a petition of James Rumsey, praying that an exclusive privilege may be granted him for constructing sundry engines, devices, and improvements, which he has discovered and invented, for the advancement of labor and useful works, agreeable to the descriptions and models thereof, accompanying his petition.

Ordered, That the said petitions do lie on the table.

Source

Journal of the House of Representatives of the United States, 1789-1793 (Friday, September 18, 1789). LINK

September 24, 1789

President Washington signs into law the (first) Judiciary Act of 1789, which establishes the federal court system.

Read more about early patent appeals to the Supreme Court

a) Duffy, John F., “The Festo Decision and the Return of the Supreme Court to the Bar of Patents” (2002). 1 Supreme Court Review 273-342 (2002); Faculty Publications. 850. LINK Copyright c 2002 by the authors. The William and Mary Law School Scholarship Repository.

b) For a detailed study of the Supreme Court decisions during the time the Justices were “riding circuit” go to the Federal Judicial Center website. LINK

c) See also “The Role of Circuit Courts in the Formation of United Sates Law in the Early Republic – Following Supreme Court Justices Washington, Livingston, Story and Thompson,” Hart Publishing, Oxford and Portland, Oregon, 2018, by Hon. David Lynch (retired from the UK Circuit Bench on the South Eastern Circuit on 31 January 2005).

September 24, 1789

President Washington nominates John Jay as the first Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. Jay would be confirmed on September 28 and begin his tenure on October 19 (continuing until June 29, 1795).

January 8, 1790

George Washington delivers the First Annual Message to a joint session of Congress, encouraging Congress to consider the “advancement of Agriculture, Commerce and Manufactures by all proper means.”

Excerpt

to discern and provide against invasions of them;

Read more about patents during the Washington administration

Mount Vernon (LINK).

February 14, 1790

Thomas Jefferson accepts appointment as Secretary of State (confirmed by the Senate on September 26, 1789).

Background

Source

Apr. 10, 1790 (1 Stat. 109-112) – Feb. 20, 1793

April 10, 1790

About one year after the government begins operation, on April 10, 1790, Congress approves “An Act to promote the progress of useful Arts” (The Patent Act of 1790 (1 Stat. 109-112)), thereby establishing the first federal patent system.

Excerpt

[U]pon the petition of any person or persons to the [Patent Board; that is, the] Secretary of State [Thomas Jefferson], the Secretary for the department of war [Henry Knox], and the Attorney General of the United States [Edmund Randolph], setting forth, that he, she, or they, hath or have invented or discovered any useful art, manufacture, engine, machine, or device, or any improvement therein not before known or used, and praying that a patent may be granted therefor, it shall and may be lawful to and for the Secretary of State, the Secretary for the department of war, and the Attorney General, or any two of them, if they shall deem the invention or discovery sufficiently useful and important, to cause letters patent to be made out in the name of the United States, to bear teste by the President of the United States … .

Source

For a copy of the bill (H.R. 41; March 10, 1790): see the U.S. Capitol Visitor Center (Exhibitions – Knowledge) – based on Records of the U.S. Senate, National Archives and Records Administration. LINK

Read more about the Patent Act of 1790:

P.J. Federico, Operation of the Patent Act of 1790, 18 J. Pat. Off. Soc’y 237, 238 (1936).

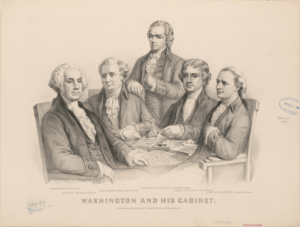

The statute provides for a Patent Board to review petitions for patents and issue patents thereon if deemed deserving. Members of the Patent Board are the Secretary of State [Thomas Jefferson], the Secretary for the department of war [Henry Knox], and the Attorney General of the United States [Edmund Randolph].

Source

For the drawing of Washington’s first cabinet: see Library of Congress. LINK

Discussion

A decision of the Patent Board could not be appealed.

April 17, 1790

Benjamin Franklin passes away.

June 27, 1790

Thomas Jefferson writes to Benjamin Vaughn about his experience on the Patent Board

Source

National Archives (LINK).

Excerpt

An act of Congress authorizing the issuing patents for new discoveries has given a spring to invention beyond my conception. Being an instrument in granting the patents, I am acquainted with their discoveries. Many of them indeed are trifling, but there are some of great consequence which have been proved by practice, and others which if they stand the same proof will produce great effect.

July 31, 1790

First patent is granted to Samuel Hopkins.

3 patents are granted in 1790; 33 patents in 1791; 11 in 1792; and, 20 in 1793.

February 7, 1791

Thomas Jefferson drafts a bill to repeal the 1790 Patent Act which would influence aspects of the 1793 Patent Act.

Read more about Jefferson's draft:

Edward C. Walterscheid, Patents and the Jeffersonian Mythology, 29 J. Marshall L. Rev. 269 (1995). LINK.

December 5, 1791

Alexander Hamilton delivers the “Report on the Subject of Manufactures” to Congress. He recommends a system for providing “premiums” “to induce the prosecution and introduction of useful discoveries, inventions, and improvements” and “not less than three” “Commissioners” to manage it.

Excerpt

Let a certain annual sum, be set apart, and placed under the management of Commissioners, not less than three, to consist of certain Officers of the Government and their Successors in Office.

Let these Commissioners be empowered to apply the fund confided to them—to defray the expences of the emigration of Artists, and Manufacturers in particular branches of extraordinary importance—to induce the prosecution and introduction of useful discoveries, inventions and improvements, by proportionate rewards, judiciously held out and applied—to encourage by premiums both honorable and lucrative the exertions of individuals, And of classes, in relation to the several objects, they are charged with promoting—and to afford such other aids to those objects, as may be generally designated by law.

The Commissioners to render [to the Legislature] an annual account of their transactions and disbursments; and all such sums as shall not have been applied to the purposes of their trust, at the end of every three years, to revert to the Treasury. It may also be enjoined upon them, not to draw out the money, but for the purpose of some specific disbursment.

It may moreover be of use, to authorize them to receive voluntary contributions; making it their duty to apply them to the particular objects for which they may have been made, if any shall have been designated by the donors.

There is reason to believe, that the progress of particular manufactures has been much retarded by the want of skilful workmen. And it often happens that the capitals employed are not equal to the purposes of bringing from abroad workmen of a superior kind. Here, in cases worthy of it, the auxiliary agency of Government would in all probability be useful. There are also valuable workmen, in every branch, who are prevented from emigrating solely by the want of means. Occasional aids to such persons properly administered might be a source of valuable acquisitions to the country.

The propriety of stimulating by rewards, the invention and introduction of useful improvements, is admitted without difficulty. But the success of attempts in this way must evidently depend much on the manner of conducting them. It is probable, that the placing of the dispensation of those rewards under some proper discretionary direction, where they may be accompanied by collateral expedients, will serve to give them the surest efficacy. It seems impracticable to apportion, by general rules, specific compensations for discoveries of unknown and disproportionate utility.

The great use which may be made of a fund of this nature to procure and import foreign improvements is particularly obvious. Among these, the article of machines would form a most important item.

The operation and utility of premiums have been adverted to; together with the advantages which have resulted from their dispensation, under the direction of certain public and private societies. Of this some experience has been had in the instance of the Pennsylvania society, [for the Promotion of Manufactures and useful Arts;] but the funds of that association have been too contracted to produce more than a very small portion of the good to which the principles of it would have led. It may confidently be affirmed that there is scarcely any thing, which has been devised, better calculated to excite a general spirit of improvement than the institutions of this nature. They are truly invaluable.

Source

National Archives (LINK).

March 1792

A memorandum by Henry Remsen, Jr., Clerk, is delivered to Secretary of State Jefferson summarizing the affairs of the “Board of Arts.”

Source

Joseph Barnes (James Rumsey’s attorney and brother-in-law) publishes “Treatise on the Justice, Policy, and Utility of Establishing an Effectual System of Promoting the Progress of Useful Arts, By Assuring Property in the Products of Genius.”

Source

Feb. 21, 1793 (1 Stat. 318) – July 3, 1836

February 21, 1793

Congress approves the Patent Act of 1793 (1 Stat. 318, “An Act to promote the progress of useful Arts; and to repeal the act heretofore made for that purpose.”). The second federal patent system is established.

The 1793 Act abolishes the Patent Board, replacing it with a system whereby patents are granted, without prior examination.

Excerpt

“when any person or persons, being a citizen or citizens of the United States, shall allege that he or they have invented any new and useful art, machine, manufacture or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement on any art, machine, manufacture or composition of matter, not known or used before the application, and shall present a petition to the Secretary of State, signifying a desire of obtaining an exclusive property in the same, and praying that a patent may be granted therefor, it shall and may be lawful for the said Secretary of State, to cause letters patent to be made out in the name of the United States … .”

Discussion

For interfering applications, the Act (Sec. 9) provided “[t]hat in case of interfering applications, the same shall be submitted to the arbitration of three persons, one of whom shall be chosen by each of the applicants, and the third shall be appointed by the Secretary of State.”

Patent disputes are resolved by the judiciary.

November 16, 1793

Thomas Jefferson writes to Eli Whitney, granting him a patent on the cotton gin (issued March 14, 1794).

Source

National Archives (LINK).

January 5, 1794

Thomas Jefferson resigns as Secretary of State. Edmund Randolph succeeds him.

September 19, 1796

George Washington’s Farewell Address.

Excerpt

“Promote then, as an object of primary importance, institutions for the general diffusion of knowledge. In proportion as the structure of a government gives force to public opinion, it is essential that public opinion should be enlightened.”

March 4, 1797

John Adams is inaugurated as the second President of the United States. His administration lasts until March 4, 1801.

December 14, 1799

George Washington passes away.

February 4, 1801

John Marshall begins his term as the fourth Chief Justice of the United States. His term as Secretary of State ends on March 4, 1801, with the inauguration of Thomas Jefferson.

March 4, 1801

Thomas Jefferson is inaugurated as the third President of the United States. His administration lasts until March 4, 1809.

May 2, 1801

Thomas Jefferson appoints James Madison as Secretary of State.

June 1, 1802

Dr. William Thornton is appointed by Secretary of State James Madison as the first Superintendent of Patents for a Patent Office in the State Department. He would serve until 1828.

Source

USPTO (LINK).

July 12, 1804

Alexander Hamilton is killed.

March 4, 1809

James Madison is inaugurated as the fourth President of the United States. His administration lasts until March 4, 1817.

February 1, 1810

Tyler v. Tuel, 10 U.S. (6 Cranch) 324 (1810) is decided. It is the first patent decision published by the U.S. Supreme Court. It concerns the assignment of a patent dated February 20, 1800.

Source

1810

Thomas Green Fessenden publishes “An Essay on the Law of Patents for New Inventions.”

Source

Hathi Trust (LINK).

Discussion

Fessenden’s “Essay,” discusses Tyler v. Tuel.

Fessenden’s cousin, Samuel C. Fessenden, would be appointed the sixth Examiner-in-Chief on the Board that would be created by the Patent Act of 1861.

August 13, 1813

Thomas Jefferson recalls his time on the “Patent-board” in a letter to Isaac McPherson “on the subject of mr Oliver Evans’s exclusive right to the use of what he calls his Elevators, Conveyers, and Hopper-boys.”

Excerpt

Considering the exclusive right to invention as given not of natural right, but for the benefit of society, I know well the difficulty of drawing a line between the things which are worth to the public the embarrassment of an exclusive patent, and those which are not, as a member of the Patent-board for several years, while the law authorized a board to grant or refuse patents, I saw with what slow progress a system of general rules could be matured. Some however were established by that board. … [B]ut there were still abundance of cases which could not be brought under rule, until they should have presented themselves under all their aspects; and these investigations occupying more time of the members of the board than they could spare from higher duties, the whole was turned over to the judiciary, to be matured into a system, under which everyone might know when his actions were safe and lawful. instead of refusing a patent in the first instance, as the board was authorized to do, the patent now issues of course, subject to be declared void on such principles as should be established by the courts of law. this business however is but little analogous to their course of reading, since we might in vain turn over all the lubberly volumes of the law to find a single ray which would lighten the path of the Mechanic or Mathematician. it is more within the information of a board of Academical professors, and a previous refusal of patent would better guard our citizens against harrassment by lawsuits. but England had given it to her judges, and the usual predominancy of her examples carried it to ours.

Source

Read More

(a) Of the several patents Oliver Evans received, see e.g., US Patent 3X, granted Dec. 18, 1790;

(b) for a petition for patent see National Archives (LINK);

(c) Jefferson approved the congressionally-passed “An Act for the Relief of Oliver Evans” on January 21, 1808 (source: Library of Congress (LINK));

(d) the second-fifth patent cases decided by the U.S. Supreme Court related to the 1808 Act:

Evans v. Jordan; Morehead, 13 U.S. (9 Cranch) 199 (1815).

Evans v. Eaton, 16 U.S. (3 Wheat.) 454 (1818).

Evans v. Hettich, 20 U.S. (7 Wheat.) 453 (1822).

Evans v. Eaton, 20 U.S. (7 Wheat.) 356 (1822).

See P. J. Federico, “The Patent Trials of Oliver Evans,” 27 J. Pat. Off. Soc’y. 657, 664 (1945).

(e) Ferguson, Eugene S., “Oliver Evans – Inventive Genius of the American Industrial Revolution,” The Hagley Museum, 1980 by the Eleutherian Mills-Hagley Foundation, Inc., 72 pages;

(f) Oliver Evans was inducted in the National Inventors Hall of Fame ™ in 2001.

March 4, 1817

James Monroe is inaugurated as the fifth President of the United States. His administration lasts until March 4, 1825.

1822

Thomas Green Fessenden publishes the second edition of “An Essay on the Law of Patents for New Inventions.”

Source

Hathi Trust (LINK).

Discussion

(a) This edition is dedicated to Justice Story and includes an analysis of his patent decisions.

(b) The “rules as may appear best to prevent, as far as possible future disputes, on the subject” proposed in the First Edition of the Essay are greatly expanded, e.g., adding “9. The speculation of a philosopher, or mechanician, which has never been put into actual operation will not deprive a subsequent inventor of his patent monopoly.”

March 4, 1825

John Quincy Adams is inaugurated as the sixth President of the United States. His administration lasts until March 4, 1829.

July 4, 1826

John Adams and Thomas Jefferson pass away.

April 12, 1828

Thomas P. Jones, appointed by Secretary of State Henry Clay, begins service as the second Superintendent of Patents for the Patent Office in the State Department. He would serve until June 10, 1829.

Source

USPTO (LINK).

March 4, 1829

Andrew Jackson is inaugurated as the seventh President of the United States. His administration lasts until March 4, 1837.

June 11, 1829

John D. Craig is appointed by Secretary of State Martin Van Buren as the third Superintendent of Patents for the Patent Office in the State Department. He would serve until January 31, 1835.

Source

USPTO (LINK).

February 1, 1835

James C. Pickett is appointed by Secretary of State John Forsyth as the fourth Superintendent of Patents for the Patent Office in the State Department. He would serve until April 30, 1835.

Source

USPTO (LINK).

June 15, 1835

Henry L. Ellsworth is appointed by Andrew Jackson as the fifth (and last) Superintendent of Patents. Superintendent Ellsworth would become the first Commissioner of Patents upon the passing of the 1836 Patent Act. He would serve until 1845.

Source

USPTO (LINK).

January 29, 1836

Patent Office Superintendent Henry L. Ellsworth responds by letter to “the inquiries made by the Hon. Chairman of the Committee on the Patent Office in the Senate [Senator John Ruggles], and referred by the Hon. Secretary of State [John Forsyth] to the Office for my report in part.”

Ellsworth recommends (a) “vest[ing] in the head of the Patent Bureau or some other a discretion to arrest a pending application for a Patent, if it interferes with any prior Patent, or caveat on file, and also if the application is destitute of novelty” or (b), in the case of interferences, three indifferent arbitrators“.

Excerpt

There are a great number of cases arising out of the Patent law before the United States Courts. How much will the number be increased when the eight hundred patents granted this year, shall appear with their many interfering specifications. There will be a rich harvest for the Lawyers but how many honest Mechanics and Inventors will be ruined by the expense of litigation. Is there no remedy? … I would respectfully suggest the following remedy. To vest in the head of the Patent Bureau or some other a discretion to arrest a pending application for a Patent, if it interferes with any prior Patent, or caveat on file, and also if the application is destitute of novelty.

…

While cupidity induces Patentees to connect their improvements with the inventions of others, ostensibly claiming all as their own, it is certainly proper that the Government should annex some penalty to such impositions. A judgment against the validity of the Patent is a suitable penalty.

Should it appear objectionable to confer the power of arresting interfering applications on the head of the Patent Bureau, the objection may perhaps be lessened by referring the interference to three indifferent arbitrators skilled in the art in question and as the arbitrators might make an improper award an appeal could be allowed to the Secretary of State or other tribunal.

The present mode of appointing arbitrators in interfering applications is to allow each party to choose one and the Secretary of State the third. This makes a board of strong bias as each applicant generally selects a particular friend. I ought to add that at present there is no compensation allowed or paid arbitrators. Each applicant might be required to pay a reasonable fee to be fixed by law. Interferences will generally be found to arise from ignorance or fraudulent interests. Information will correct the former, while a rigid scrutiny will induce impostors to withdraw their pretensions.

Source

April 28, 1836

Senator John Ruggles (“Father of the United States Patent Office”) submits the “Report Accompanying Senate Bill No. 239,” 24th Cong., 1st Sess. (April 28, 1836) wherein he proposes “to give the Patent Office a new organization … a board of examiners [‘to which an appeal may be taken’].”

Excerpt

A necessary consequence is, that patents even for new and meritorious inventions are so much depreciated in general estimation that they are of but little value to the patentees, and the object of the patent laws, that of promoting the arts by encouragement, is in a great measure defeated.

To prevent these evils in future is the first and most desirable object of a revision and alteration of the existing laws on this subject. The most obvious, if not the only means of effecting it, appears to be to establish a check upon the granting of patents, allowing them to issue only for such invention as are in fact new and entitled, by the merit of originality and utility, to be protected by law. The difficulty encountered in effecting this, is in determining what the check shall be; in whom the power to judge of inventions before granting a patent can safely be reposed, and how its exercise can be regulated and guarded, to prevent injustice through mistake of judgement or otherwise, by which honest and meritorious inventors might suffer wrong.

It is obvious that the power must, in the first instance, be exercised by the department charged with this branch of the public service. But as it may not be thought proper to intrust its final exercise to the department, it is deemed advisable to provide for an occasional tribunal to which an appeal may be taken. And as a further security against any possible injustice, it is thought proper to give the applicant in certain cases, where there may be an adverse party to contest his right, an opportunity to have the decision revised in a court of law.

The duty of examination and investigation necessary to a first decision at the Patent Office, is an important one, and will call for the exercise and application of much scientific acquirement and knowledge of the existing state of the arts in all their branches, not only in our own, but in other countries. Such qualifications in the officers charged with the duty, will be the more necessary and desirable, because the information upon which a rejection is made at the office, will be available in the final decision. It becomes necessary, then, to give the Patent Office a new organization, and to secure to it a character altogether above a mere clerkship. The competency and efficiency of its officers should correspond with their responsibility, and with the nature and importance of the duties required of them. …

A power in the Commissioner of the Patent Office to reject applications for want of novelty in the invention, it is believed, will have a most beneficial and salutary effect in relieving meritorious inventors, and the community generally, from serious evils growing out of the granting of patents for every thing indiscriminately, creating interfering claims, encouraging fraudulent speculators in patent rights, deluging the country with worthless monopolies, and laying the foundation for endless litigation.

In nineteen cases out of twenty, probably, the opinion of the Commissioner, accompanied by the information on which his decision is founded, will be acquiesced in. When unsatisfactory, the rights of the applicant will find ample protection in an appeal to a board of examiners, selected for their particular knowledge of the subject-matter of the invention in each case.

Source

University of New Hampshire, Franklin Pierce School of Law, IP Mall. (LINK)

June 28, 1836

James Madison passes away.

July 4, 1836 (5 Stat. 117–125) – Mar. 1, 1861

July 4, 1836

Congress passes the “An Act to promote the progress of useful arts, and to repeal all acts and parts of acts heretofore made for that purpose.” Patent Act of 1836 (5 Stat. 117-125)). This establishes the third federal patent system, the examination framework of which is still adhered to to this day.

Excerpt

Source

Discussion

Sec. 7 of the 1836 Patent Act provides for an appeal to “a board of examiners”.

Sec. 8 provides that the Commissioner decides questions regarding an application interfering with another application or “unexpired patent” and “if either [party] shall be dissatisfied with the decision of the Commissioner on the question of priority of right or invention, on a hearing thereof, he may appeal from such a decision [to the Board].

Excerpt

Read more on the evolution of appeals vis-a-vis the Commissioner:

Discussion

Even when the law was changed to transfer jurisdiction of patent appeals to the Chief Judge of the District Court of the District of Columbia (1839 Patent Act) and assistant judges of the Circuit Court of the District of Columbia (1852 Patent Act), the Commissioner remained bound by the decisions on appeal.

The Patent Act of 1861, which established a permanent Board of Appeals within the Patent Office to hear appeals from adverse decisions of examiners, provided for an appeal from the Board to the Commissioner. The Commissioner was not bound by decisions of the Board. Applicants could appeal the Director’s decision to the District Court for the District of Columbia.

By the Patent Act of 1927, the Commissioner was added as a member of the Board. An applicant dissatisfied with a decision of the Board could no longer appeal the Board’s decision to the Commissioner but “may appeal to the Court of Appeals of the District of Columbia” (Sec. 8). Today such appeals are to the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit.

December 15, 1836

Fire destroys the Patent Office, located in Blodget’s Hotel since 1810. Patent Office relocates to the D.C. City Hall at Judiciary Square, now District Court of Appeals.

March 3, 1837

Congress approves the Act of March 3, 1837 which requires the Commissioner of Patents to transmit an annual report of the Patent Office to Congress.

This Act also enlarged the Patent Office to 25 employees.

March 4, 1837

Martin Van Buren is inaugurated as the eighth President of the United States. His administration lasts until March 4, 1841.

January 14, 1839

Commissioner Ellsworth submits the first Patent Office Report for 1838 to Congress (25th Congress, 3rd Session, H.R. Doc. No. 80) Due in part to inconsistent decision-making by the various individuals appointed, Commissioner Ellsworth recommends “substitut[ing] for the board of examiners, the expediency of allowing an appeal to the chief justice of this District [i.e., the Chief Judge of the District Court of the District of Columbia].

Excerpt

The board of examiners, occasionally appointed in cases of appeals, is attended with inconveniences, not foreseen, which ought, if possible, to be corrected. This tribunal was provided, it is presumed, to relieve the apprehensions some might have entertained, from the power necessarily conferred, and the duty imposed upon the Commissioner, to withhold a patent in every case where the claim is destitute of merit or originality. Contrary, perhaps, to the intention of the framers of the law, it has been construed to open the whole matter, on appeal, to the reception of additional evidence, leading to much delay and expensive litigation before the board.

The compensation provided for this board of examiners appears to have been predicated upon the idea of a brief and summary duty, and is so small that few of requisite qualifications are found who will consent to undertake it.

Hence much delay arises in constituting a board, whenever an appeal is made; and different individuals being appointed in different cases, their rules and course of proceedings are various and unsettled. The examination into the originality of an invention, or supposed discovery, preliminary to the issuing of a patent, and the settling of interfering claims to patents, must necessarily be, in some measure, summary. But the decision between contesting parties is, in all cases, subject to judicial corrections; and a final adjudication is, by law, as it ought to be, referred to the courts.

It is submitted whether the Commissioner could not be authorized to prescribe, with advantage, the necessary rules for the taking of testimony to be used in hearing before him; and to make suitable regulations for a full and fair hearing of all parties interested.

As a remedy for the evil alluded to, (of which parties complain,) I beg leave to suggest, as a substitute for the board of examiners, the expediency of allowing an appeal to the chief justice of this District, giving him power to examine and determine the matter summarily at chambers, or otherwise, on the evidence From the experience had, thus far, it may be presumed that the judge would have but few cases to examine, and that those would not materially interfere with his other a judicial duties. A reasonable compensation for such duty may be made from the patent fund. Parties from a distance could then have their cases settled, without great delay or trouble to which they are now subjected.

Source

March 3, 1839

Congress approves “An Act in addition to ‘An act to promote the progress of the useful arts’” (the Patent Act of 1839 (5 Stat. 353-355)).

The 1839 Patent Act repeals the provision for an appeal to “a board of examiners” in the Patent Act of 1836.

A right of appeal is taken to the Chief Judge of the District Court of the District of Columbia, i.e., Chief Judge William Cranch.

Excerpt

Sec. 11. [I]t shall be the duty of said chief justice, on petition, to hear and determine all such appeals, and to revise such decisions in a summary way, … Provided, however, That no opinion or decision of the judge in any such case, shall preclude any person interested in favor or against the validity of any patent which has been or may hereafter, be granted, from the right to contest the same in any judicial court, in any action in which its validity may come in question.

Read more about Chief Judge William Cranch

Discussion

His son, William G. Cranch, was an examiner in the patent office:

• (a) Barnard, J. (1922). History of the Church of the New Jerusalem in the City of Washington. Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C., 24, 23-42 (LINK);

• (b) see, e.g., the Official Register of the United States covering September 30, 1841 through September 30, 1843 (LINK).

March 4, 1841

William Henry Harrison is inaugurated as the ninth President of the United States. His administration lasts until April 4, 1841.

April 4, 1841

John Tyler is inaugurated as the tenth President of the United States. His administration lasts until March 4, 1845.

1842

Patent Office relocates from the D.C. City Hall at Judiciary Square, now District Court of Appeals, to the Patent Office Building (F and G Streets and 7th and 9th Streets, N.W., Washington, D.C.).

March 4, 1845

James K. Polk is inaugurated as the eleventh President of the United States. His administration lasts until March 4, 1849.

May 5, 1845

Edmund Burke, appointed the second Commissioner of Patents by President Polk. He would serve until May 9, 1849.

Source

USPTO (LINK)

January 1849

Commissioner Burke submits the 1848 Patent Office Report to Congress (30th Congress, 2nd Session, House Ex. Doc. No. 59). Commissioner Burke raises a concern about the imposition of patent office appeals on Chief Judge William Cranch.

Source

Hathi Trust (LINK)

Excerpt

The increasing business of the Patent Office has added so much to the duties imposed upon the Chief Justice of the District, who was by the act of March 3, 1837 [sic., 1839], constituted a court of appeals from the decisions of the Commissioner of Patents, that the present compensation which he receives for that service is wholly inadequate to the labor which he is required to perform. He now receives $100 per annum as the judge of appeals from the Patent Office. Within the knowledge of the undersigned there has been a single case before the chief justice involving an amount of labor and time, which, if devoted to any other pursuit requiring the same talents and attainments for its execution, would have commanded treble the sum he receives for his services in that capacity for the whole year. It would be just, therefore, that the present compensation of the chief justice should be increased to an amount which would be adequate to the duties and labors which the law imposes upon him.

March 4, 1849

Zachary Taylor is inaugurated as the twelfth President of the United States. His administration lasts until July 9, 1850.

May 4, 1849

Thomas Ewbank, appointed by President Taylor, begins service as the third Commissioner of Patents for the Patent Office in the Interior Department. He would serve until November 1, 1852.

Source

May 22, 1849

Abraham Lincoln is granted U.S. Patent 6469 for an “Improved Method for Buoying Vessels Over Shoals.”

Source

Abraham Lincoln Online (LINK)

July 9, 1850

Millard Filmore is inaugurated as the thirteenth President of the United States. His administration lasts until March 4, 1853.

May 1, 1851

The first world’s fair – The International Exhibition “embracing all manufactures” – opens in The Crystal Palace in Hyde Park, London; conceived by the Society of Arts of England. Closes October 15, 1851; 6,039,195 visitors.

Source

Reports of the Commissioners of the United States to the International Exhibition held at Vienna, 1873, p. 34 (via Hathi Trust) (LINK)

August 30, 1852

Congress approves “An Act in addition to An Act to Promote the Progress of the Useful Arts” (the Patent Act of 1852 (1 Stat. 318)).

By this Act, appeals of decisions of the Commissioner of Patents from appeals of decisions of the examiner could now also be made “to either of the assistant judges of the Circuit Court of the District of Columbia,” in addition to the Chief Judge.

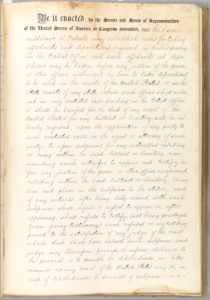

Excerpt

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That appeals provided for in the eleventh section of the act entitled An Act in addition to an act to promote the progress of the useful arts, approved March the third, eighteen hundred and thirty-nine, may also be made to either of the assistant judges of the Circuit Court of the District of Columbia, and all the powers, duties, and responsibilities imposed by the aforesaid act, and conferred upon the chief judge, are hereby imposed and conferred upon each of the said assistant judges.

Sec. 2. And be it further enacted, That in case appeals shall be made to the said chief judge, or to either of the said assistant judges, the Commissioner of Patents shall pay to such chief judge or assistant judge the sum of twenty-five dollars, required to be paid by the appellant into the Patent-Office by the eleventh section of the said act, on said appeal.

Sec. 3. And be it further enacted, That section thirteen of the aforesaid act, approved the third, eighteen hundred and thirty-nine, is hereby repealed.

November 2, 1852

Silas Henry Hodges, appointed by President Fillmore, begins service as the fourth Commissioner of Patents for the Patent Office in the Interior Department. He would serve until 1853.

He would be appointed by Abraham Lincoln as one the first three Examiners-in-Chief (1861).

Source

USPTO (LINK)

March 4, 1853

Franklin Pierce is inaugurated as the fourteenth President of the United States. His administration lasts until March 4, 1857.

July 23, 1855

Abraham Lincoln writes to Peter H. Watson, patent attorney representing John H. Manny (sued for patent infringement by Cyrus H. McCormick) indicating “I can devote some time to the case.” Also associated with this case were Edwin M. Stanton, future Secretary of War under Lincoln, and George Harding, whom Lincoln would nominate as the first Examiner-in-Chief for a new Board in the Patent Office established by the Patent Act of 1861, albeit Harding would decline the position.

Source

Collected works. The Abraham Lincoln Association, Springfield, Illinois. Roy P. Basler, editor; Marion Dolores Pratt and Lloyd A. Dunlap, assistant editors. Lincoln, Abraham, 1809-1865. New Brunswick, N.J: Rutgers University Press, 1953, volume 2, p. 315

Laura Cielo, Director of Communications and Development, St. Peter’s Episcopal Church in Philadelphia: website entry of April 25, 2017

February 11, 1856

Charles Mason, appointed by President Pierce in 1853 as the fifth Commissioner of Patents, submits the 1855 Patent Office Report to Congress (34th Congress, 1st Session, House Ex. Doc. No. 12). Commissioner Mason would serve until 1857.

Source

USPTO (LINK)

In the 1855 Patent Office Report, Commissioner Mason explains that “[i]n case of the rejection of an application, the law and the practice of the office permit an appeal to the Commissioner, and finally to one of the judges of the circuit court of the District. But such appeals are attended with much trouble and expense … .” He proposes appointing “an examiner-in-chief [or three] whose sole duty would be to review the actions of the present examiners, with a view of introducing correctness and uniformity of decision.”

Excerpt

In case of the rejection of an application, the law and the practice o the office permit an appeal to the Commissioner, and finally to one of the judges of the circuit court of the District. But such appeals are attended with much trouble and expense, so that, in most cases, especially where the applicant resides at a distance, a rejection by the examiner is, in point of fact, final. Under such circumstances, the importance of correctness and uniformity of decision upon the first examination can hardly be too highly appreciated. They cannot reasonably be hoped for under the system now in operation, and the more that system is extended the greater the evil becomes.

To remedy this difficulty several plans have been suggested, but they generally resolve themselves into one of the two following, or modifications thereof:

1st. The appointment of an examiner-in chief, whose sole duty would be to review the actions of the present examiners, with a view of introducing correctness and uniformity of decision. As a modification of this plan, it has been sometimes proposed to increase the number of examiners-in-chief to three, some one of whom should make a final decision upon each of the various questions, which should first be fully and clearly presented by some of the members of the corps of examiners as now constituted, and who might all three act conjointly on appeals and other cases of unusual difficulty.

2d. To return to the former practice of the office, making the duties of the examiners simply advisory, and allowing a patent in all cases, provided the applicant should finally insist upon it, notwithstanding the opinion of the office as to its invalidity.

The main objection to the former of the above plans grows out of the difficulty of obtaining competent and suitable persons to fill the chief places. I doubt whether there is a situation under the government for which it would be more difficult to find a suitable incumbent. Qualities would be required for the satisfactory discharge of such a duty which are rarely found united — a well-trained capacity for comprehending and investigating all subjects connected with natural and mechanical philosophy, and a high order of legal acumen and experience. The difficulty is still further increased by the fact, that very few of our lawyers have ever turned their attention in this direction. The law relating to patents is less understood by the profession than any other branch of that noble science. And as the cherished rights of inventors are to be submitted to the sound discretion of these officers, habits of patient and laborious investigation and the high moral qualifications of integrity and impartiality are quite as indispensable as those of an intellectual character.

Source

Hathi Trust (LINK)

January 3, 1857

Scientific American publishes an editorial regarding “another Patent Bill [that] has been drawn up, and will shortly be reported to Congress. … The principle features of the New Bill to which we have alluded, are, if we are correctly informed, as follows – … Appoints a Board of Appeal.”

Excerpt

“Important from Washington. – Another New Patent Bill before Congress … [The Bill proposes to appoint] a Board of Appeal, consisting of three Chief Examiners, with a salary each of $3,500 per annum. It is to be their duty to entertain all appeals from the decisions of the examiners, in cases where inventors think that injustice has been done them in the rejection of their applications. No fee for such appeals. From the decisions of this Board further appeal may be taken to the Commissioner on the payment of a small fee.

[This feature will give satisfaction provided the proper individuals are placed upon the Board. Some of the oldest and most experienced among the examining officers, and who would, perhaps, expect, on the ground of experience and seniority, to he appointed, are, to their discredit, the most illiberal in their feelings towards inventors and in their interpretation of the Patent Laws of any persons in the department. None of your conceited, crabbed, mulish, illiberal-minded individuals – men who never see anything new – who are always prone to regard one device as but the mechanical equivalent for another- with whom the “double use” of a thing is a continual stumbling block – such men should never be put upon the proposed Board. We want fresh, liberal, energetic persons, who will interpret the Patent Laws in their most liberal sense.

Some such Board as the above is needed, for the present duties which devolve upon the Commissioner are greater than any one man can or ought to be required to perform. The proposed Board would relieve him very much, and, if properly constituted, be of great advantage to inventors.]”

Source

Scientific American, January 3, 1857, Volume XII, Number 17, page 130 (Hathi Trust) (LINK)

March 4, 1857

James Buchanan is inaugurated as the fifteenth President of the United States. His administration lasts until March 4, 1861.

November 1857

A temporary board of appeals consisting of three examiners-in-chief drawn from primary examiners in the Patent Office is organized.

Source

Commisionner Holt’s 1858 Patent Office Report to Congress (35th Congress, 2nd Session, Senate Ex. Doc. No. 47) (LINK)

January 20, 1858

Joseph Holt, appointed on September 10, 1857 by President Buchanan as the sixth Commissioner of Patents, submits the 1857 Patent Office Report to Congress ( 35th Congress, 1st Session, Senate Ex. Doc. No. 30).

Commissioner Holt recommends “that there shall be appointed a permanent board of three examiners-in–chief.”

Commissioner Holt would serve until March 14, 1859.

Excerpt

Whatever might be the capabilities of the Commissioner for physical and mental labor, it would be impossible for him to discharge the administrative duties of his office, and hear, in person, all the appeals brought before him from the decisions of examiners. The usage has hence grown up of referring he investigation of most of these appeals to a board, constituted or the occasion, consisting of two or more examiners, who make their report to the Commissioner. As these boards lack permanence, and from necessity, indeed, have been constantly changing, without a critical examination of each report by the Commissioner, which is not practicable, uniformity in action and in the assertion of principle cannot be maintained. To prevent in future that conflict, which has been so often deplored in the past, it has been recommended that there shall be appointed a permanent board of three examiners-in-chief, who shall be charged with the duty of hearing and determining upon all appeals from the judgment of the primary examiners. Such a tribunal would, no doubt, attain the end sought, and the members of it should their appellate duties not fully occupy their time could, by the Commissioner, be assigned labor in the classes requiring such assistance with much advantage to the public service.

Source

Re the excerpt goto Hathi Trust.

Re Commissioner Holt goto USPTO.

January 31, 1859

Abraham Lincoln delivers his first lecture on Discoveries and Inventions to the Young Men’s Association of Bloomington, Illinois. A second rewritten version would be delivered in February 1859 before the Phi Alpha Society of Illinois College at Jacksonville, Illinois and before the Springfield Library Association.

Source

Collected works. The Abraham Lincoln Association, Springfield, Illinois. Roy P. Basler, editor; Marion Dolores Pratt and Lloyd A. Dunlap, assistant editors. Lincoln, Abraham, 1809-1865. New Brunswick, N.J: Rutgers University Press, 1953, volume 3, pp. 357-363. (LINK)

Commisioner Holt submits the 1858 Patent Office Report to Congress (35th Congress, 2nd Session, Senate Ex. Doc. No. 47).

Commissioner Holt notifies Congress that “a board” “consisting of three examiners” and “occupied in the examination of appeals from the decisions of the primary examiners to the Commissioner” was “temporarily organized” in November 1857. Commissioner Holt suggests “legalization of this board” so as not to impose “the responsibilities of examiners-in-chief on examiners.”

Excerpt

Since the month of November, 1857, a board temporarily organized, and consisting of three examiners, specially detailed for this duty, have been occupied in the examination of appeals from the decisions of the primary examiners to the Commissioner. During the past year they investigated and disposed of 535 cases, in most of which they have submitted elaborately prepared reports. The results of their action have been eminently satisfactory, and have commanded, it is believed, the entire confidence of the country. The withdrawal of these officers from their respective classes has practically reduced the examining corps to nine instead of twelve, the number at which it was fixed in 1856. The applications of that year amounted to 4,960, those of 1858 amounted to 5,364, so that with a reduced force there is a heavy increase of the labor to be performed. This is unfortunate and to be deplored in reference alike to the public and the inventor. The former has a deep interest in that thorough and faithful examination of applications contemplated by the patent laws, in order that rights which belong to all may not be unjustly monopolized by one; the latter has the same interest, lest a patent, hastily and incautiously granted, should prove, in his hands, but a lure to draw him into harassing and impoverishing litigation. The legalization of this board, and the restoration of examiners to the three classes now virtually deprived of them, would furnish at once the relief required.

Since the establishment of this temporary board of appeals, the classes from which its members were respectively withdrawn have been in charge of those who have the rank and pay of assistant examiners only. In the new position, however, assigned them they have had imposed upon them the responsibilities of examiners in chief, and it is due to them to say that they have discharged their duties with zeal and fidelity. In my judgment, it is but just that they should be compensated according to the character of the services they have rendered. Assistant examiners similarly circumstanced were provided for by Congress in 1856, and I commend the claims of those now referred to to your favorable consideration.

Source

Hathi Trust (LINK)

May 23, 1859

William Darius Bishop is appointed by President Buchanan as the seventh Commissioner of Patents for the Patent Office in the Interior Department. He would serve until January 1860.

Source

Biographical Directort of the United States Congress. (LINK)

December 11, 1859

Senator William Bigler of Pennsylvania introduces Senate Bill S.10, “in addition to ‘An Act to promote the progress of the Useful Arts’.” It is referred to the Senate Committee on Patents and the Patent Office on January 24, 1860.

The Bill (Sec. 2) provides for a board of three Examiners-in-Chief appointed “in the same manner as now provided by law for the appointment of examiners [i.e., by the Commissioner].” NB. Per Sec. 2 of the Patent Act of 1836, examiners were appointed by the Commissioner – this is retained in Sec. 2 of the bill.

Sec. 2 of the bill prohibits appeals from the Commissioner to the Judiciary. See debate of April 16, 1860 (excerpts below).Sec. 3 of the bill allows appeals from Primary Examiners to the Examiners-in-Chief only after an application has been twice rejected (“second examination”). See debate of May 26, 1860 (excerpts below).

Excerpt

Section 2. And be it further enacted, that, for the purpose of securing greater uniformity of action in the grant and refusal of letters patent, there shall be appointed, in the same manner as now provided by law for the appointment of examiners, a board of three Examiners-in-Chief, at an annual salary of three thousand dollars each, to be composed of persons of competent legal knowledge and scientific ability, where duty it shall be, on the written petition of the applicant for that purpose being filed, to revise and determine upon the validity of decisions made by examiners when adverse to the grant of letters patent, and also to revise and determine in like manner upon the validity of the decisions of examiners in interference cases, and to perform such other duties as may be assigned to them by the Commissioner; that from the decisions of this board of appeals may be taken to the Commissioner of Patents in person, upon payment of the fee hereinafter prescribed; that the said examiners-in-chief shall be governed in their action by the rules to be prescribed by the Commissioner of Patents. No appeal shall hereafter be allowed from the decision of the Commissioner of Patents, except in cases pending prior to the passage of this act.

Source

Library of Congress (LINK)

February 16, 1860

Philip Francis Thomas, appointed by President Buchanan, begins service as the eighth Commissioner of Patents for the Patent Office in the Interior Department. He would serve until December 10, 1860.

Source

Biographical Directort of the United States Congress (LINK)

April 16, 1860

Senate debates Senate Bill No. 10, particularly as it concerns the proposed board of examiners-in-chief and appeals to the Commissioner and then to the judiciary.

Excerpt

Motion to strike from the bill “No appeal shall thereafter be allowed from the decision of the Commissioner of Patents, except in cases pending prior to the passage of this act” agreed to.

Source

The Congressional Globe, 36th Congress, 1st Session; pp. 1731-1733 (LINK)

May 26, 1860

Senate continues debate over Senate Bill No. 10.

NOTE Senator’s Hale’s proposed amendment to change assigning the appointment of Examiners-in-Chief from the Commissioner to the President, by and with the advice of the Senate, is agreed to and becomes part of the bill.

Excerpt

Senator Grimes: “I move to strike out the third section. This is the section which requires that before an appeal shall be allowed to the examiners-in-chief, the application shall be twice rejected by the subordinate examiners. I do not see any necessity for imposing that increased expense upon the applicants. … Then it must be known to gentlemen who are familiar with the Patent Office, that these subordinate examiners are not the most profoundly scientific men in the world, and good cases may be rejected by them; and we ought not to subject the applicants for patents, who are generally poor, but worthy men, to the loss of time and additional expense they must incur in making a second application, in order to get their case carried up from some ignoramus who may be placed there as a subordinate examiner from political considerations solely, before gentlemen who have some knowledge of science and the arts.”

Senator Bigler: “I prefer very much to rest my support of it upon the opinion of three or four Commissioners, with the most experienced men in the various details there, all of whom concur in this bill throughout. I am not willing to see the section stricken out, for I have no doubt its operations are well understood in the Department, and will be advantageous.”

…

So the motion was not agreed to.

Senator Hale: “There is one amendment that I desire to propose; and I wish to have the ear of the Senate for about a minute, while I state it. The second section of this bill proposes to provide for the appointment of a board of three examiners-in-chief … and assigns very important duties to them. By the bill, they are to be appointed by the Commissioner. They are to stand between the Commissioner and other examiners, and are an independent board, and I think ought to be appointed by the President, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate.”

Senator Bigler: “I see no special objection to the amendment of the Senator from New Hampshire. There are those who have felt that this department was peculiarly independent, belonging to the people, self-reliant, they paying all the expenses themselves, and having no connection with the Treasury, or any other Department here, and that it should be kept independent within itself as possible. Perhaps that would be the only suggestions that could be made against the amendment. For my part, I do not care how the Senator decide it.

…

The amendment was agreed to.

Source

The Congressional Globe, 36th Congress, 1st Session; p. 2364 (LINK)

Bill No. 10 (engrossed) is passed. (Click on image for full view.) This would become the law (12 Stat. 246-249 (March 2, 1861)) establishing what we now call “the Board.” The Senate concurred to the House’s amendment to strike “board” and leave it as “examiners-in-chief.” It would revert to a “board” via 16 Stat. 198-217 (July 8, 1870).

Source

Image: (LINK)

July 2, 1860

A Bureau of Interferences and Extension is established by the Commissioner.

Excerpt

The Commissioner of Patents has established a special bureau to hear and determine Interference cases and applications for Extensions; thus relieving the Examiners and tending to render the decisions of the Patent Office in those cases more uniform than they have heretofore been. This arrangement is an excellent one, and has long been needed. Up to the present time it has been the practice to require the Examiners to take charge of and decide all Interference cases arising in their respective classes, subject to the approval of the Commissioner. But so greatly has the general business of the Office and the number of new applications made for patents increased, that the Examiners find themselves unable to give proper attention to Interferences and Extensions without neglecting or postponing other cases of importance. The bureaus just established will therefore greatly relieve them.

The Bureau of Interferences and Extensions has been placed under the charge of Examiner Henry Baldwin, who is more particularly known at the Patent Office as Judge Baldwin. We regard this appointment as an excellent one. Judge Baldwin is one of the oldest and most experienced officers in the department, and he is fully qualified to discharge the important duties of the newly-created bureau with success.

The Patent Office — take it altogether — is, at the present time, in a highly flourishing condition; and its officers, with a few exceptions, exhibit in their official views and actions a uniform and commendable liberality of disposition toward inventors. In these respects a very marked change has been observable within the last three years, an alteration we attribute, in a great degree, to the wisdom and firmness which has characterized the labors of the Board of Appeals. There has been no change in this board; the members are Messrs. Lawrence, Little and Rhodes.

No institution of the kind in the world presents a better organization or administration than that of the United States Patent Office as now constituted.

Source

IP Mall (Scientific American, Vol. 3, No. 1, p. 10, 2 July 1860) (LINK)

Board of Examiners-In-Chief

Mar. 2, 1861 (12 Stat. 246-249) – July 7, 1870

March 2, 1861

“An Act in Addition to ‘An Act to promote the Progress of the Useful Arts [Patent Act of 1836]” (12 Stat. 246-249 (1861)) becomes law.

Discussion

The examiners-in-chief are “to be composed of persons of competent legal knowledge and scientific ability.”

on the written petition of the applicant for that purpose being filed, to revise and determine upon the validity of decisions made by examiners when adverse to the grant of letters-patent;and also to revise and determine in like manner upon the validity of the decisions of examiners in interference cases,

and when required by the Commissioner in applications for the extension of patents,

and to perform such other duties as may be assigned to them by the Commissioner.”

“from their decisions may be taken to the Commissioner of Patents in person, upon payment of the fee hereinafter prescribed.

It also provides “that the said examiners-in-chief shall be governed in their action by the rules to be prescribed by the Commissioner of Patents.”

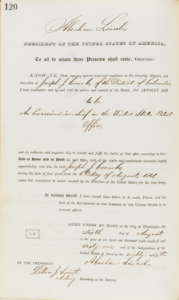

March 4, 1861

Abraham Lincoln is inaugurated as the sixteenth President of the United States.

March 25, 1861

March 28, 1861

David Pierson Holloway is appointed by President Lincoln as the ninth Commissioner of Patents for the Patent Office in the Interior Department. He would serve until August 17, 1865.

Source

April 12, 1861

Fort Sumter, Charleston, South Carolina, is attacked. The American Civil War begins.

June 25, 1861

In Snowden v. Pierce, 2 Hay. & Haz. 386 (1861), Chief Judge James Dunlop, who succeeded William Cranch as Chief Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, holds that “[u]nder the Act of March 2, 1861, the primary examiners and the examiners-in-chief, are by the terms of the Act recognized as judicial officers, acting independently of the Commissioners who can only control them when their judgments in due course come before them on appeal.”

Excerpt

“A preliminary question has been raised as to my jurisdiction of this case, the same having been decided on the 6th of March, 1861, four days after the passage of the Act of March 2, 1861, entitled “an Act in addition to an Act to promote the useful arts.” I will give my views generally of the true construction of this Act of March 2, 1861, and then of the special circumstances attending the decision of this case in the office.

Previous to the passage of the Act of March 2, 1861, all judicial acts done in the Patent Office, by the primary examiner or the Board of Appeals, organized under office regulations, were in intendment of law, the judicial acts of the Commissioners, and had no legal validity till sanctioned by him. The primary examiners and Board of Appeals under the old system were the organs of the Commissioner to inquire and enlighten his judgment and until the Commissioner gave validity to their judicial acts by his fiat, they had no legal existence 2& judgments.

Under the Act of March 2, 1861, the primary examiners and the examiners-in-chief, are by the terms of the Act recognized as judicial officers, acting independently of the Commissioners who can only control them when their judgments in due course come before them on appeal.

The Commissioner, under the Act of March 2, 1861, can give no judgment till the appeal reaches him, and this cannot be done till the judgment of the primary examiner has first been submitted to the examiners-in-chief.

The Judges of the Circuit Court of the District of Columbia, by law can entertain no appeal except from the decisions of the Commissioner. All the decisions of the office, whether by examiners or the old Board of Appeals were in law, the decisions of the Commissioner when sanctioned by him.— When a primary examiner under the old system refused a patent, or decided an interference case, and the Commissioner approved such decision, an appeal lay directly to one of the Judges from such decision of the Commissioner; not so under the new law of 1861. The primary examiners and the examiners-in-chief are all, by the Act of 1861, treated as judicial officers having power without control, within the sphere of their duty, to the exercise of their independent judgment. Their acts under the new law are not as under the old system the acts of the Commissioners, but their own acts. They are no longer the mere organs of the Commissioner but independent officers. He can only reach and overrule them when their judgments come regularly before him on appeal.

It follows therefore that no judgment now in any patent case, of the character above described can be given by the Commissioner till it reaches him in due course by appeal, that is to say, the applicant must go from the primary examiner by appeal to the examiners-in-chief, and from them by appeal to the Commissioner, and lastly from the. Commissioner to one of the Judges of the Circuit Court.

The appeal to the Judges lies from the Commissioner under the old system, and has not been expressly taken away. We have no right to infer or conclude that it has been taken away by implication by the creation of the Appeal Board of Examiners-in-chief, with the right of appeal from them to the Commissioner. All such implication is repelled by the fact, well known, that an express repealing clause in the Act of 1861, on its passage through the legislature, was stricken out.

I think there is no repugnancy between the appeals given by the Act of 1861 and the ultimate appeal to the Judges, they may all stand together. The ultimate appeal to the Judges is the same appeal which originally, under the old law, laid to the old Board of Examiners, outside of the office appointed by the Secretary of State.

This appeal extended to all final decisions of the Commissioner refusing an applicant a patent, or determining an interference, and was afterwards transferred to the Judges of the Circuit Court. I think this appeal to the Judges still exists, but it can only be exercised after the applicant has gone the rounds of all the tribunals created by the new law, and after decision of the Commissioner.

I do -not think, however, under the particular circumstances of this case, the applicant, Snowden, was first bound to have gone to the examiner-in-chief under the new law, and then to the Commissioner, before coming to me. His case was submitted to the Commissioner before the passage of the Act of March 2d, 1861. All the testimony had been taken and closed, the arguments made, and the case in the hands of the Commissioner for decision, before March 2d, 1861. To apply the Act to such a case would give it a retrospective operation. I entertain no doubt, therefore, that I have therefore regularly jurisdiction of this appeal.”

July 5, 1861

President Lincoln nominates Joseph J. Coombs as the fourth Examiner-in-Chief (to fill the seat George H. Harding declined to take). In April, 1861, Coombs had applied for U.S. District Attorney for the District of Columbia, but General Edward C. Carrington (1825-1892) was appointed instead (of whose appointment Coombs opposed in a letter to Lincoln on account Carrington’s involvement in the Fisher affair).

President Lincoln nominates Joseph J. Coombs as the fourth Examiner-in-Chief (to fill the seat George H. Harding declined to take). In April, 1861, Coombs had applied for U.S. District Attorney for the District of Columbia, but General Edward C. Carrington (1825-1892) was appointed instead (of whose appointment Coombs opposed in a letter to Lincoln on account Carrington’s involvement in the Fisher affair).

On August 6, 1861, President Lincoln appoints Coombs by recess appointment. Coombs is issued an Executive Commission with a 4-year term.

Source

Regarding Coombs’s application for District Attoney, see Library of Congress

Regarding the Fisher affair, see Library of Congress – Lincoln Correspondence – Joseph J. Coombs opposes appointment of Edward Carrington and University of Oklahoma College of law – American Indian and Alaskan Native Documents

December 3, 1861

Abraham Lincoln delivers his first annual message. He recommends Congress “find an easy remedy for many of the inconveniences and evils which constantly embarrass those engaged in the practical administration of [statute laws]. Since the organization of the Government Congress has enacted some 5,000 acts and joint resolutions, which fill more than 6,000 closely printed pages and are scattered through many volumes.” This would lead to the Revised Statutes (1870-1878).

February 13, 1862

Commissioner Holloway transmits to Congress the Patent Office Report of 1861. In it, he propose that the law “should be so amended as to render the duties of the examiner-in-chief advisory only, so that an appeal, as formerly, may be taken from the examiner or from the Commissioner to the circuit court.”

Excerpt

Proposed Amendments [to the Patent Act of March 2, 1861] … The avowed object of the second section of the act of the 2d of March, 1861, is ‘securing greater uniformity of action in the grant and refusal of letters patent.’ This is attempted to be effected by the creation of three examiners-in-chief, whose duty it is made to ‘revise and determine upon the validity of decisions made by examiners when adverse to the grant of letters patent, and in interference cases.’ It was expected by this means to relieve the Commissioner of a portion of the labor of the duties of office imposed upon him, but has utterly failed to secure this last-named object.

As now constituted under the law, the examiners-in-chief form a tribunal independent of the Commissioner in all cases of rejection or interference decided by the examiner. An appeal lies from the examiner to them, from them to the Commissioner, and from him to one of the judges of the circuit court of the District of Columbia.

The chief justice has decided that an appellant must go through each tribunal before the judge of the circuit court can take jurisdiction of the case.

This state of the law and practice is far from beneficial to the public, and does not tend to secure greater uniformity of action in the grant or refusal of letters patent, and does certainly greatly augment the labor of the Commissioner. The act, in my opinion, should be so amended as to render the duties of the examiner-in-chief advisory only, so that an appeal, as formerly, may be taken from the examiner or from the Commissioner to the circuit court. All appeals should be taken from the decision of the examiner directly to the Commissioner, who could then refer it to the examiners-in-chief, or, if his time permitted, hear it in person.”

June 17, 1862

In a failed effort to clarify that the Board is not independent but rather simply advisory, Rep. Dunn from the Committee on Patents reports on an amendment to H.R. 365 (“An act to promote the progress of the useful arts”) which reads, in part:

In a failed effort to clarify that the Board is not independent but rather simply advisory, Rep. Dunn from the Committee on Patents reports on an amendment to H.R. 365 (“An act to promote the progress of the useful arts”) which reads, in part:

[Sec. 1] “That from an after the passage of this act the three examiners-in-chief created by the act of March 2, 1861, to which this is additional, shall not constitute an independent tribunal in the Patent Office to revise and determine upon the validity of the decisions made by the Commissioner of Patents in the refusal of letters patent, or in interference cases, but that the duties of said examiners-in-chief shall be only advisory to the Commissioner of Patents, who shall prescribe rules for their action.”

Source

Congressional Globe; 37th Congress, 2nd Session, pp. 2762-2763. (image linked to debate on the amendment)

July 17, 1862

Senate considers H.R. 365 (“An act to promote the progress of the useful arts”) and strikes out Sec. 1. (Congressional Globe; 37th Congress, 2nd Session, p. 3403.)

March 3, 1863

“An act to promote the progress of the useful arts” is enacted into law (H.R. 365 without Sec. 1); 12 Stat. 796 (1863).

This statute provides, in part, that every patent must be dated no later than six months from allowance with final fee paid, otherwise “the invention therein described shall become public property.”

April 9, 1865

The American Civil War ends at Appomattox Court House, Virginia.

April 15, 1865

Abraham Lincoln is assassinated.

Andrew Johnson is inaugurated as the seventeenth President of the United States. His administration lasts until March 4, 1869.

August 1, 1865

Andrew Johnson appoints Elisha Foote as the fifth Examiner-in-Chief (to fill the seat rendered vacant by the termination of Joseph J. Coombs’ 4-year commission (July 15, 1865)).

August 17, 1865

Thomas Clarke Theaker, who had been appointed by Lincoln as one the first three Examiners-in-Chief, resigns and begins service as the tenth Commissioner of Patents for the Patent Office in the Interior Department. He would serve until January 20, 1868.

Source

November 23, 1865

Samuel C. Fessenden is appointed by Andrew Johnson as the sixth Examiner-in-Chief, filling the seat vacated by Thomas Clarke Theaker.

Samuel Fessenden is the cousin of Thomas Green Fessenden who published “An Essay on the Law of Patents for New Inventions” (1810 and 1822), the first treatise on U.S. patent law.

April 5, 1868

Andrew Johnson appoints Benjamin F. James as the seventh Examiner-in-Chief.

He would be the first Primary Examiner (Engineering Class) to be appointed an examiner-in-chief.

July 23, 1868

“An act to authorize the temporary Supplying of Vacancies in the Executive Department” becomes law. 4oth Congress, Sess. II, Chap. 227. It provided “That in the case of the death, resignation, absence, or sickness of the commissioner of patents, the duties of said commissioner, until a successor be appointed or such absence or sickness shall cease, shall devolve upon the examiner-in-chief in said office oldest in length of commission.”

July 28, 1868

Elisha Foote resigns as Examiner-in-Chief to become the 11th Commissioner of Patents, a position he would hold until April 25, 1869.

March 4, 1869

Ulysses S. Grant is inaugurated as the eighteenth President of the United States. His administration lasts until March 4, 1877.

April 21, 1869

Ulysses S. Grant appoints Rufus L. B. Clarke as the 8th Examiner-in-Chief.